The following is an abstract I wrote for the completion of my training in Thomas Hübl’s Collective Trauma Facilitator Training. In which we were asked to write about a topic to deepen our understanding of collective trauma. Of course, I chose something body-oriented. Enjoy!

“People are trapped in History, and History is trapped in them.” -James Baldwin

What is Embodiment?

The word originates from the Latin-derived prefix em, meaning "in" or "make into," and the Old English word bodig, meaning "physical frame" or "trunk."

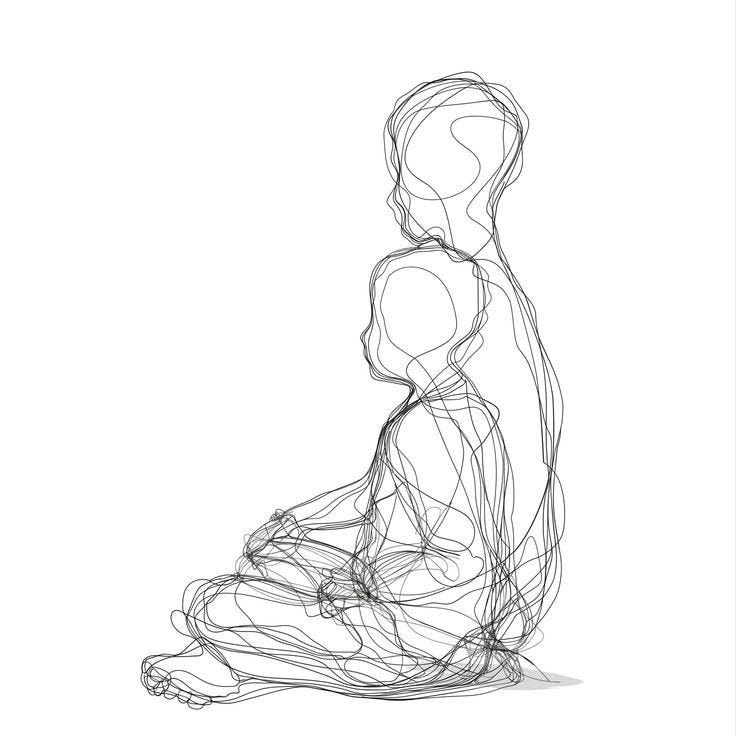

What inhabits the body? Is it neurobiological, mechanical, or informational - learning how to walk, run, speak, or read? Or is it emotional, energetic, ancestral? An identity, a soul, or awareness itself coming into form?

Perhaps more interestingly, who is doing the “making into physical form?” And if we can embody, there must also be a significance in the alternative, disembodiment. I’m curious about how the intelligence of life lies in both, how we can become aware of their respective processes, and what becoming aware does for both our past and future.

Embodiment is a sexy word of these times, but what does it mean? Why is it supportive to participate in embodiment practices? And how do they serve our collective becoming? Beyond individualistic wellness culture narratives of “feeling better” or neo-spiritual ideals of personal transcendence, can embodiment give us access to freedom here and now? What is the function of disembodiment in our collective? What does fascia have to do with ancestral memory and the felt sense of interconnection, of community, of belonging? These are some of the questions I will explore here.

This essay proposes that fascia is not only an organ of biomechanical function but a relational archive—storing individual, ancestral, and collective memory—and that somatic embodiment practices offer a method for collective restoration, integration, and futuring.

This essay proposes that fascia is a relational archive and carrier of information across time zones - the individual, ancestral, and collective. This primary force of embodiment can offer availability for collective restoration, integration, and futuring.

To understand how embodiment operates across generations, we begin by looking at how fascia plays a part in organizing our experience.

Fascia as the Organ of Embodied Intelligence

Fascia is the body’s organ of form. It is the sheath of connective tissue, made mostly out of collagen, elastin, and water, that supports and upholds the structure of the body and its relationship with gravity. Without fascia, we would be a disorganized sack of fluids and bones (Schleip, 2021).

However, fascia doesn’t only hold everything together, it also creates just the right spacing in the body for cells to communicate, organs to function, joints to articulate, and muscles to compress and lengthen. Every cell in the body is connected to fascia so it acts as an inner GPS - important for proprioception, interoception, and neuroception.

Proprioception: The ability to sense the body in space and how it moves. This is possible because deep fascial layers contain more sensory nerves than muscles themselves. Cells transport postural and coordination information through fascia to the brain via these mechanoreceptors (Schleip et al., 2006).²

Interoception: The internal sense of the body. Including emotions, pain, hunger, thirst, temperature, etc. This is possible through fascial lines registering chemical, pressure, and visceral changes, and sending these sensations to the brain (Craig, 2002).³

Neuroception: The body’s subconscious scanning for safety. The vagus nerve, essential in Polyvagal Theory, influences social engagement based on the perception of safety or threat.

A deficit in proprioception can cause disorientation and dissociation, while poor interoception and neuroception underlie emotional dysregulation and social withdrawal. Therefore, in traumatic experiences, fascia plays a key role in creating the defense, disorientation and sympathetic nervous system activation, which could be used to describe the process of disembodiment. If not attended to, a pattern of holding, fighting, fleeing, or freezing becomes chronic, getting stored in mechanical, inflammatory, and metabolic cell memory. Such cellular adaptations can be transmitted through epigenetic modifications across generations.4

Moreover, as the vagus nerve travels from the brain down to the abdomen, innervating different organs, it moves within fascial sheaths, specifically the visceral and carotid fascia. When fascia is stimulated through somatic practice, including breathwork, intentional movement, and touch, its mechanoreceptors help downregulate the nervous system.6

There’s growing research in the bidirectional influence of this vagal-fascia axis, where chronic stress and traumatic experience are levers in dysregulation. As new science emerges, we are starting to update our linear lens of the body with real insight into its biodynamic nature. That one function affects another in a continuous feedback loop.

Fascia as Community

As one part of the body shuts down or contracts (i.e., less movement), other parts compensate. Nothing is isolated. A restriction in the pelvic floor may echo into the jaw; a braced diaphragm may influence the arches of the feet. The fascial system is a key interface across this ecosystem, acting like a fiber-optic communication network.

The fascial web allows the body to operate as an intelligent whole, constantly adapting and reorganizing itself. Yet this same intelligence, when shaped by generational trauma, can organize around fragmentation, rigidity, and collapse. The body’s organization around responses to stress echoes in the fascia of future generations, which then tend to react viscerally to stimuli that mimic anything close to what was experienced in the past.

We can see fascia as a communal organ of not only individual bodies but also collections of bodies. It’s the body’s version of the village record keeper. Nothing is lost. Nothing is forgotten. Fascia gives us access to information beyond the time zone we inhabit. Through its intimate relationship with each cell of the body, the passed-down information can continue to be used as an organizing force.

If we are unaware of how the past organizes us, we are susceptible to history repeating itself. With awareness, the stress responses of the past can be tended to, and ancestral resiliency used appropriately. This awareness is made possible through embodiment practice.

The body itself exists within a communal network of relational intelligence, a collective fascia of sorts. We will now stretch beyond our tendency to think of embodiment as a personal practice to include its ancestral and collective application.

Embodiment as a Collective Practice

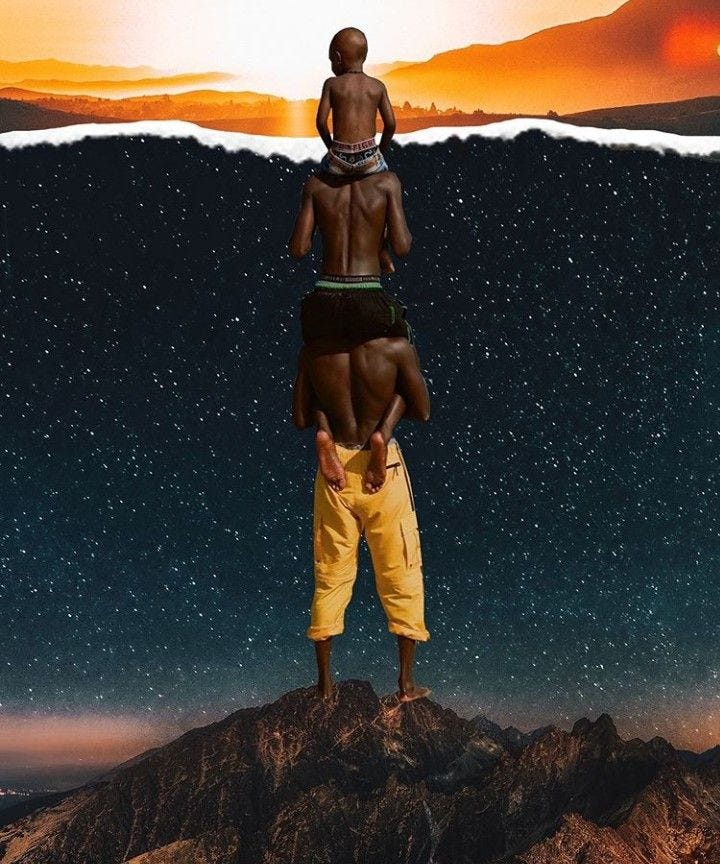

We often think of our bodies as ours - “I have a body”. However, memory stored in the fascia speaks to how much our personality structure, i.e. natural reactions, postures, expressions, pain, and nervous system tone, evolved through an ancestral and collective body. A direct transmission comes from our parents’ and grandparents’ bodies. Both the resources and the stressed/frozen parts.

Therefore, the embodiment practices we undertake are not only about releasing held tensions. They are also about harvesting information from the experiences of our ancestors, accessing resources, and restoring movement and sensation to places that were necessarily cut off.

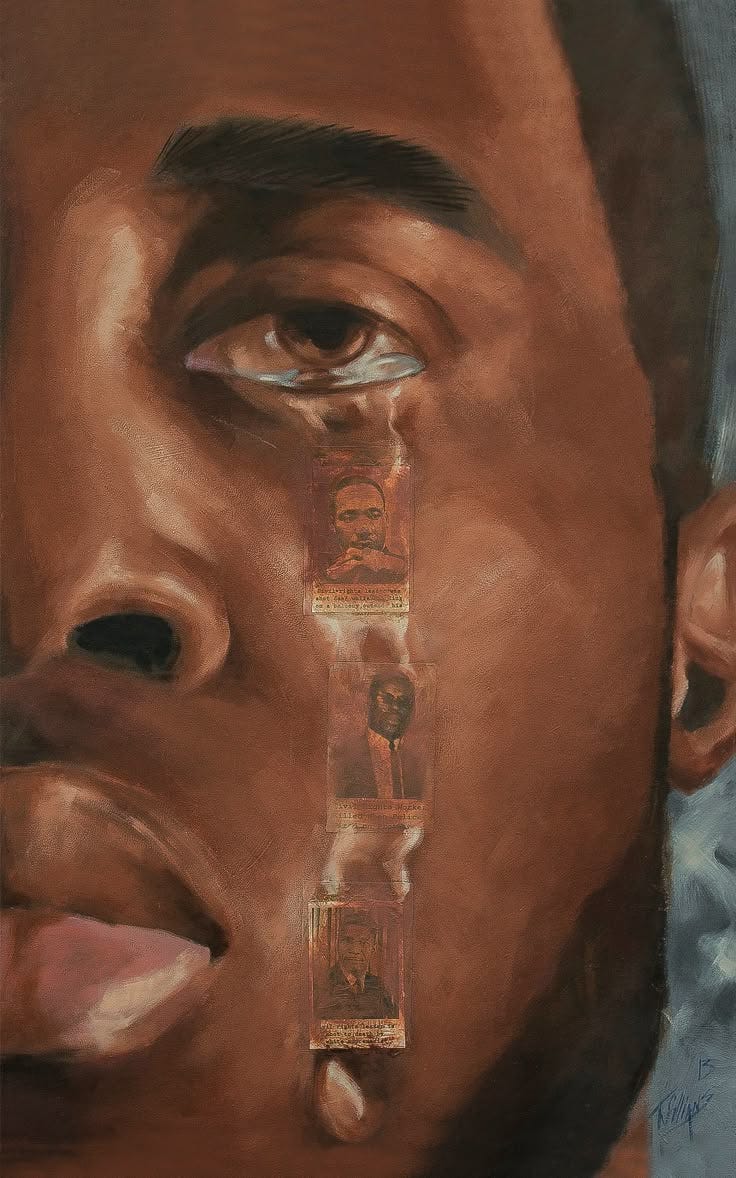

Consider groups of people who come from ancestors who experienced subjugation in the body for generations. The compensations and plasticity needed to be transmitted through bodies that were captured, deported, shackled, beaten, tortured, worked past their limits, raped, experimented on, and in many other unimaginable ways, abused and exploited, became the soil upon which their kin sprouted into existence.

Many of these adaptations and ways of functioning became what we now call “culture.” We can see this, generally speaking, in how different communities become distinct in the ways they relate to the world. So the race, nation, class, community, and family we are born into is important in shaping our ability to sense our bodies, which emotions are permitted and which are looked at as dangerous, and how we ought to move in the world.

These blueprints are interrogated in embodiment practices. We can participate in practices such as yoga, qi gong, martial arts, dance, breathwork, meditation, etc. to come into contact with reality, with presence. To make direct contact with the moment opens us up to possibilities untethered by the past. Maintaining relation to the body becomes a way of futuring, of innovating. Going beyond the strategies of the past and becoming free to create.

Embodiment is both an individual and a collective movement. It’s about remembering, restoring, informing, and becoming from the inside out.

The Power of the Collective Defense

Our learned ability to turn off or freeze parts of the body is a strong intelligence. In these cases, the fascial web develops what is called “fuzz”, coined by Dr. Gil Hedley, which prohibits the sliding and gliding of tissues over one another.7 More than the physical, the lack of hydration in these areas decreases self-sensing capabilities. The shutoff becomes protection in not feeling, giving us the ability to turn away. We become absent from those parts of our body - we “move out of” the body.

The power in this movement is that when there was no choice to physically remove themselves from painful situations, the ancestors could still be partially distant from the moment by hardening feeling. Whether conscious to the person or not, the body created defenses against the inconceivable.

Millions of bodies have inherited decisions of the past to turn away from pain. In repairing and restoring past transgressions, we need to acknowledge the collective capacity to avert. Otherwise, the intelligence of disembodiment as a way of survival is missed, and we diagnose the collective body. The absence becomes something we wish to overcome, usually solely with the intellect, which takes us further into polarization and reductionist tendencies. Far away from restoration.

A collective somatic witnessing includes the awareness of fascial fuzz that has compounded body-over-body and become a fog that lies between us. Time zones of history that we don’t fully visit, and what blurs our eyes from seeing the current problems surfacing as symptoms of past missteps. The dissonance that arises as an echo of places not felt. We begin to reinhabit and soften these shut-down places in the body through a collective witness of their need in the past.

Collective Somatic Witnessing

Most of our interventions reflect our hyper-individualized culture. We seldom take into account the ecosystem where symptoms surface. Therapy, medicine, schooling, and the ways we look to develop or heal, including spiritually, become isolated and self-absorbed endeavors. We’ve been taught that the body-mind is something to fix and transcend, so we distance ourselves from the resource it has the potential to be.

Embodiment practices can restore connection to these resources. And they are much more than personal practice. In my experience, working with groups in both synchronous and asynchronous movement creates a field in which each individual's nervous system becomes a part of a collective body.

As the constellation gyrates, pulses in and out of presence, and gains greater awareness of itself as an ecosystem (i.e., people more and more feel they are a part of this collective body), the cellular memories are also unwinding. Fascial lines are moved together. Momentum and group coherence build, allowing for each body in the ecosystem to drop into what the Polyvagal system would call ventral vagal. Calm, connected, engaged, and joyfully curious.

A group experiencing this state together has the potential to move into deeper time zones than the personal. Ancestral and collective memories, usually surfacing on their own account, become available. If people in the group bring their attention to the ancestral parts of their body as they move, information will present itself. This information is always there but becomes accessible through the attunement (proprioceptive, interoceptive, and neuroceptive awareness) and space (the collective body) that a group creates.

The collective body builds a sense of belonging. It slowly breaks down the illusion of separateness as more individuals can relax their previously needed tensions and holding patterns. This begins to include the ancestral and collective defenses, where a fluidity between the personal and collective develops. As the feeling of interdependence in the field expands, the group continually surfaces more information beyond the personal - ancestors speak what was unspoken, and the group hosts the pain of collective transgressions of the past viscerally.

Group somatic witnessing becomes a space where what has been held in human bodies for generations can finally move fluidly again.

Embodied Futuring

Life has this natural movement that seems to want a more elaborate tomorrow. We can observe this movement across time. However, many of our updates and innovations are built upon shaky foundations - the stuff we haven’t cleaned up. So the shadow ends up fulfilling itself in what we call the future. As if the hardware updates, but the software stays the same.

To live into futures that lack the shadows of our past, the body needs an upgrade. We need to learn from our past to create a better soil for tomorrow. A somatic, embodied learning. Using our consciousness to become attentive to absent places in the body creates the space for the update. Cultures, nations, and communities doing this together keep side effects or symptoms out of new creations. Group somatic witnessing is a collective hygiene practice. Embodiment isn’t about being perfect, but about cleaning up as we walk.

Restoration happens within the fascia that encapsulates our muscles, organs, joints, and bones, but also is fundamental in organizing our experience. This system gives access to the past, which we can decide to use or avoid. Knowing that what we continue to turn away from will be inherited by our kin.

The future is not somewhere we go, it's something we embody. To be unburdened by our past is a freedom promised by many ancient traditions. Where the language of “moving on”, “overcoming”, and “getting on with it” transforms into inclusion. If we wish to transcend any of the problems we face today as a collective, we must be willing to look. This “we” is essential in our collective becoming. Because our level of embodiment as a human community will inform the futures we walk into.

Sources

Schleip R, Klingler W, Lehmann-Horn F. Active fascial contractility: fascia may be able to contract in a smooth muscle-like manner… Med Hypotheses. 2005;65(2):273–276.

Schleip R, Findley TW, Chaitow L, Huijing P. Fascia: The Tensional Network of the Human Body. 2006.

Craig AD. How do you feel? Interoception: the sense of the physiological condition of the body. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3(8):655–666.

Calabrò, M. et al. Transgenerational Epigenetic Inheritance of Traumatic Experience in Mammals. Int J Mol Sci. 2023; transgenerational stress exposure elicits epigenetic regulation in HPA axis and behavior across F1–F3 generations.

Hacettepe University. Relationship of Cervical Region Tension With Vagal Function. NCT05325879.

Schwartz A. Fascia and the Vagus Nerve. YogaUOnline. 2022.

Hedley, G. (2017, April 1). What’s the “fuzz” about fascial relationships? Florida School of Massage. https://floridaschoolofmassage.com/2017/04/01/whats-the-fuzz/

If you or someone you know would be interested in working with me, please see the links below for more information.

Some of the metaphors here are just a tad heavy, but I enjoyed reading, "cleaning up as we walk" is a nice image...thanks for your efforts and bringing more attention to the body! 👏

Thank you Jaden. I’m loving reading these end of training essays, by you, and others in the training. It’s a beautiful harvesting and unique how the work is expressing itself through each of you into the world.